Notes from Underground: Dostoevsky on suffering and the will to live

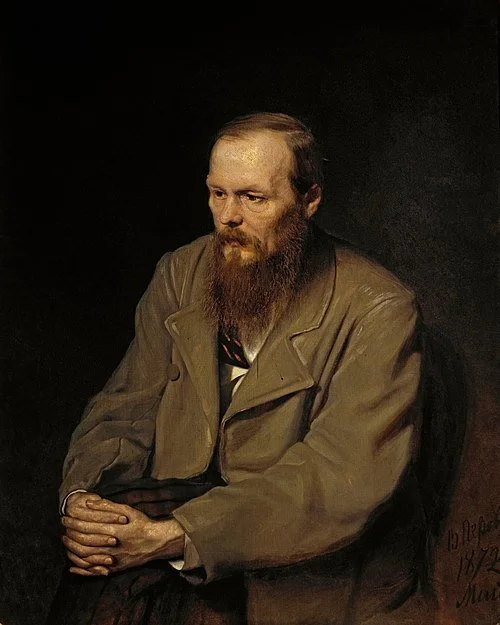

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novella Notes from Underground instantly draws you in with its opening line, “I am a sick man… I am a wicked man.” Published in 1864, the story features an unreliable narrator who’s similar to many of Dostoevsky’s protagonists: he’s obsessive, impoverished, and on the outskirts of Russian society.

In many ways, this is reflective of Dostoevsky’s own life. After his involvement with a group that discussed banned political texts, Dostoevsky was sentenced to death by firing squad under Tsar Nicholas I. At the last moment, he was spared and instead sent to Siberia for four years of hard labor, followed by six years of compulsory military service.

In Notes from Underground, the unnamed narrator (we’ll call him the “Underground Man”) reflects on his life as a low-level civil servant in St. Petersburg, hyper-fixating on social blunders he committed years prior. The result is an intense story about society, suffering, self-sabotage, and purpose.

Notes from Underground isn’t a light read, but it explores why, even in dire conditions, we continue to live.

The descent into madness

Most of Dostoevsky’s works are maddening. You don’t pick them up to be inspired or uplifted, or for a sense of resolution. They’re unusual, unsettling, and full of characters with hard lives who make bad decisions (similar to Dostoevsky, who also was a gambling addict).

But they’re chock-full of interesting ideas, and they expose us to the perspective of the ultimate outsider. In this case, the Underground Man—an isolated, undersocialized, and unhinged individual who’s the product of a broken society.

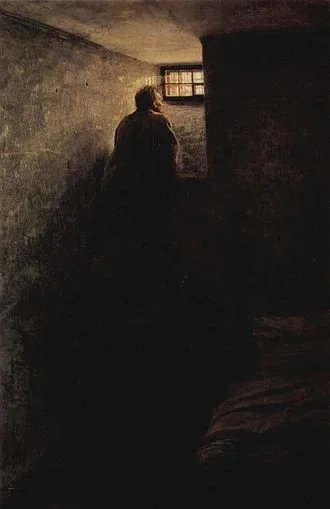

In Notes from Underground, the Underground Man is so far removed from normal society that he addresses the reader from a crack beneath his floorboard. We sympathize with him and, in some ways, relate to his feelings of isolation and futility.

Notes from Underground isn’t a traditional story. It’s split into two parts, where the first part, Underground, lacks a plot, setting, and is just the narrator sharing his life philosophy. As the Underground Man notes in a footnote, the purpose of the first section is to introduce “himself, his outlook, and seeks, as it were, to elucidate the reasons why he appeared and had to appear among us.” This section is great for those who enjoy reading philosophy.

By contrast, the second and final part of the novella, Apropos of the Wet Snow, is more conventional, with characters, setting, and a plot. It’s basically a lived out example of the narrator’s philosophy in part I, shown by his experiences.

Where to start with Dostoevsky

At just over 120 pages, Notes from Underground efficiently captures the essence of Dostoevsky's works. It very quickly gives you a sense of Dostoevsky’s writing style and the types of characters, traits, and themes he’s interested in. I found the Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky translation enjoyable too.

But if you’re new to Dostoevsky, I wouldn’t recommend starting with Notes from Underground because it’s so unconventional. Instead, I’d start with a short story like “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man” or “White Nights,” or Crime and Punishment if you prefer novels.

There’s a helpful flow chart with a recommended order for reading Dostoevsky’s works here.

***

For a brief interlude…check out these articles for more insights + subscribe to my newsletter:

Dostoevsky on why we need suffering

One of the central ideas in Notes from Underground is that humans actively choose to suffer. We don’t always act rationally or in our own best interest, and suffering becomes a counterbalance to comfort, order, and well-being. The Underground Man even suggests that “maybe suffering is just as profitable for [man] as well-being,” going so far as to argue that suffering serves a purpose happiness alone can’t fulfill.

For Dostoevsky, suffering intensifies consciousness. It sharpens our awareness and deepens our inner life. A world organized entirely around comfort and reason would leave little to feel or reflect on; suffering, by contrast, keeps us alert, restless, and painfully aware of our own existence.

That’s why the Underground Man insists, “I’m certain that man will never renounce real suffering, that is, destruction and chaos. Suffering—why, this is the sole cause of consciousness.” In this view, suffering and the narrator’s inner conflict aren’t unfortunate byproducts of life but essential to being human.

What counters despair

After establishing the necessity of suffering, the story raises a more unsettling question: why does someone with a horrible, painful life (like the Underground Man, impoverished, isolated, seemingly beyond redemption) continue to live? Why not give up entirely?

Dostoevsky’s answer doesn’t lie in hope or resolution, but in creation. He suggests that humans have an insatiable need to work towards something, anything, as a way to counter suffering. As the Underground Man notes:

“Man is predominately a creating animal, compelled to strive consciously towards a goal and to occupy himself with the art of engineering—that is, to eternally and ceaselessly make a road for himself that at least goes somewhere or other [...] and the main thing is not where it goes, but that it should simply be going.”

When one goal is reached, another quickly takes its place. What matters isn’t completion but movement. Striving gives life direction, keeping us from collapsing into despair.

This is where Dostoevsky is more unsettling than reassuring. The Underground Man’s chosen pursuits—obsessions, grudges, fixations with righting perceived wrongs—don’t liberate him. They keep him trapped. Then again, these destructive pursuits may be the only thing he has to live for.

Self-sabotage and man’s greatest vice

Interestingly, just as we’re driven to strive for something, we’re also paralyzed by that same striving. We’re intuitively afraid of achieving our goals because achievement is definite, final. And with that finality comes purposelessness—what’s next and why bother?

As the Underground Man writes:

“For he senses that once he finds it, there will be nothing to search for.” Striving keeps us alive.

What then follows is Dostoevsky’s assertion about man’s greatest vice. It’s the opposite of creation, of making roads: idleness, the refusal to strive at all. As he puts it:

Man must not “give himself up to pernicious idleness, which, as is known, is the mother of all vice. Man loves creating and the making of roads, that is indisputable.”

However misguided our pursuits may be, they’re essential. Without them, life collapses into stagnation.

Have you read Notes from Underground? More broadly, what makes a deeply introspective character interesting to you as a reader? Leave your thoughts in the comments section below!