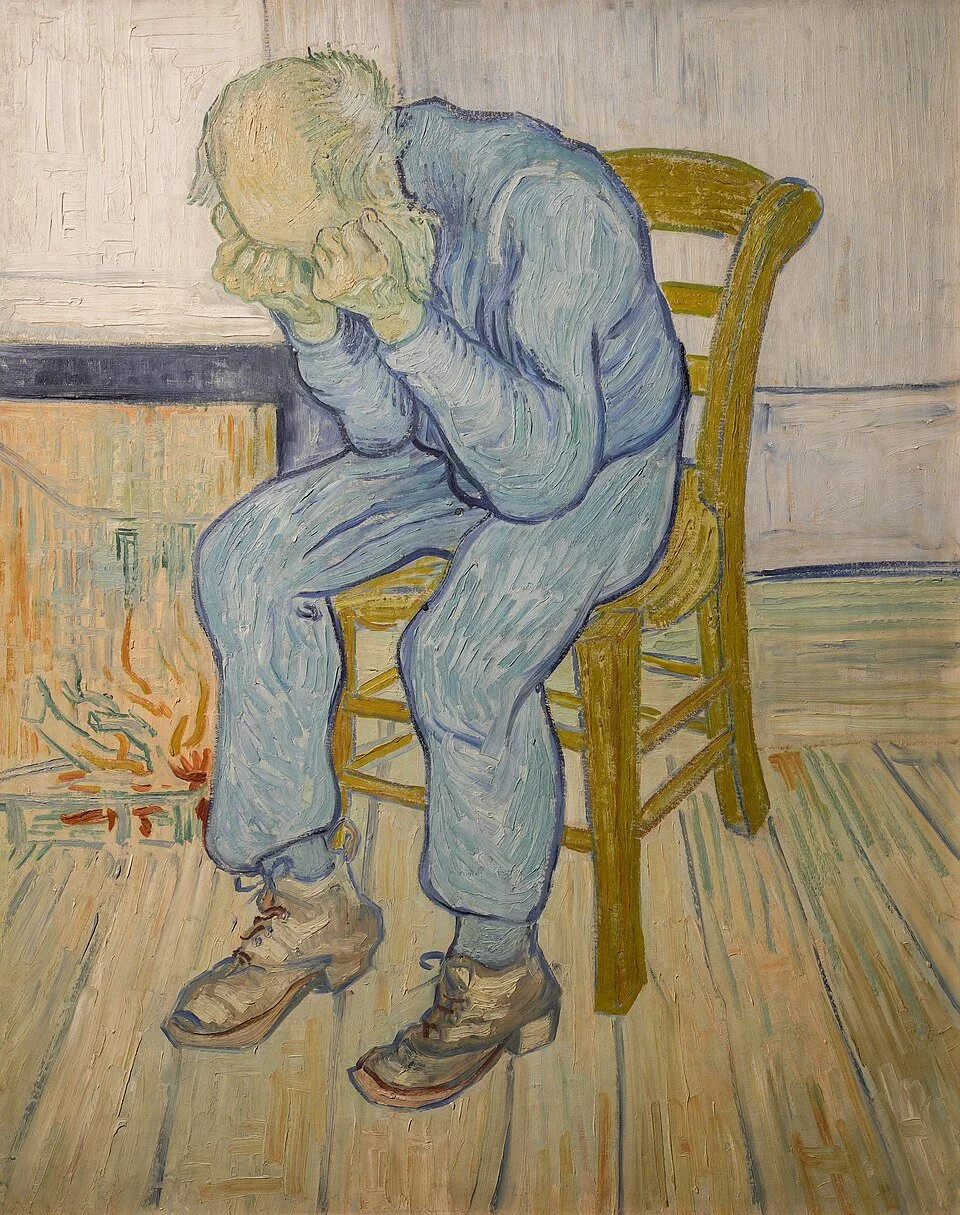

Schopenhauer on the human condition and original sin

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860) was an influential German philosopher who, despite providing the foundation for much of modern philosophy, died in relative obscurity.

His ideas inspired countless philosophers, physicists, musicians, and writers—everyone from Friedrich Nietzsche and Albert Einstein to Richard Wagner, Leo Tolstoy, and Herman Melville. Apparently at one point Einstein even kept a portrait of Schopenhauer on the wall in his study.

What was so compelling about Schopenhauer’s philosophy? What does it reveal about our inherent nature and how can we live better lives from it?

The core of Schopenhauer’s philosophy: pessimism or realism?

Schopenhauer has a reputation for being a pessimist. With writings about how we’re living “in the worst of all possible worlds,” and that “misfortune in general is the rule,” this isn’t surprising. My personal favorite is:

“No one is to be greatly envied, but many thousands are to be greatly pitied. Life is a task to be worked off.” LOL.

Yet, Schopenhauer gains credence among his supporters for his unprecedented realism. He starts by acknowledging that life is suffering (an admittedly Buddhist idea, as he was heavily inspired by the East).

Then the question becomes: in a world where suffering is the rule and happiness is fleeting, how can we go on and why should we?

But first, it’s essential to understand the core of Schopenhauer’s philosophy:

The universe is an irrational place. Humans are driven by a blind, insatiable force that governs all of reality—which Schopenhauer calls “the will.” The will compels us to survive, reproduce, and pursue our desires.

But because the will has no ultimate goal, we are caught in an endless cycle of craving and disappointment: once one desire is fulfilled, another takes its place.

Unlike Buddhism, Schopenhauer argues that there is no ultimate liberation—only temporary relief.

But by accepting that life is suffering without real end, we can weaken the grip of the will—through art, aesthetic contemplation, and compassion that offer temporary escapes from desire.

So why do we suffer from the will while other creatures don’t?

The unique—and damning—human condition

When we think about the human condition, we have to consider how humans are different from other species. And of course, what sets us apart from other animals is our intellect—our ability to reason, but also our capacity for reflection (which is crucial to Schopenhauer).

The very traits that make us unique and put us at the top of the food chain are the exact sources of our suffering. But why? We are wired to reflect on the bad—the troubles of the past and the worries of the future—and this only grows with time as we accumulate painful experiences.

Animals suffer in the moment and then move on. As Schopenhauer describes:

“The animal lacks reflection, that condenser of pleasures and pains which, therefore, cannot be accumulated as happens in the case of man by means of his memory and foresight.”

Reflection is what traps us in a cycle of misery. The intellect that gave us reason, morality, and progress also damned us with anxiety, shame, and existential dread.

Pain is proportional to knowledge

But it doesn’t stop there. Reflection doesn’t just trap us in past pain and future dread, it also gives rise to knowledge. And with knowledge comes self-awareness—we can see the truth of our condition. Unlike animals, we know that we (and the ones we love) will die some day.

This knowledge doesn’t just deepen suffering; it makes it unavoidable. We suffer not only because we are always striving, but because we know that in the end, death will undo everything we’ve strived for.

We begin to understand that everything is temporary and no amount of pleasure or progress can shield us from loss. As Schopenhauer writes:

“The measure of pain increases in man much more than that of pleasure and is now in a special way very greatly enhanced by the fact that death is actually known to him.”

We begin to see the cycle of desire and suffering for what it is: endless, empty, and inescapable. Animals perceive only the present, while we perceive absence, possibility, and time. We carry both hope and fear, such that we suffer before anything actually happens.

“The enhanced power of knowledge renders the life of man more woebegone than that of the animal, we can reduce this to a universal law and thereby obtain a much wider view. In itself, knowledge is always painless. Pain concerns the will alone and consists in checking, hindering, or thwarting this.” — Schopenhauer

***

For a brief interlude…check out these articles for more insights + subscribe to my newsletter:

The doctrine of Original Sin

Whether you’re religious or not, the Bible offers an extremely impressive diagnosis of the human condition. In the story of Adam and Eve, the first humans live in paradise—they’re free from suffering, shame, and death. The only rule they must follow is to not eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.

But they do, and are punished and cast out of paradise. Schopenhauer draws heavily on this story:

“When judging a human individual, we should always keep to the point of view that the basis of such is something that ought not to be at all, something sinful, perverse, and absurd, that which has been understood as original sin, that on account of which he is doomed to die.”

Schopenhauer’s whole premise is that knowledge is why we suffer and that pain is proportional to knowledge. The crucial point here is that these are pains we were never supposed to have.

That is the damnation of Original Sin. We’re given God-like knowledge, but that’s the extent of the godliness; the rest is still animal. It is this inherent contradiction that creates so many problems and makes the entire condition of our being suffering.

What would life be like without this condition? Is it a signal for how we should live instead?

What we need more of: compassion and presence

Schopenhauer’s entire framework rests on a bleak point: the world and our own nature make us suffer. This very fact should make us more forgiving towards others as he notes:

“The correct standard for judging any man is to remember that he is really a being who should not exist at all, but who is atoning for his existence through many different forms of suffering and through death.”

In other words, if we accept that everyone is struggling just to exist, it becomes easier to be patient, forgiving, and kind. For Schopenhauer, our response must be compassion:

“Pardon’s the word to all… We should treat with indulgence every human folly, failing, and vice, bearing in mind that what we have before us are simply our own follies, failings, and vices. For they are just the failings of mankind to which we also belong”

And to ease our own suffering, we can also take a note from the animal condition—to live in the present and not dwell on things. In this way, we can grasp momentary peace.

If suffering is built into the structure of life, how should we live in it? Share your thoughts in the comments below!